Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s been easy to forget that a number of longstanding deadly global health problems remain with us, in some cases exacerbated by the outbreak. More people are hungry this year than last; childhood vaccinations and polio eradication have taken a step back; and AIDS, malaria, and TB continue to kill millions annually. In early December, a group of public health leaders recommended an “action agenda” for the incoming Biden administration that looked at the damage done to global health programs by the pandemic and plotted a path forward. Authors of the plan, published in The Lancet, include Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Dean Michelle Williams, former Chan School Dean Barry Bloom, former Health and Human Services Secretary Donna Shalala — now a U.S. representative from Florida — and experts from Georgetown University, Emory University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Gazette recently talked with Williams about what needs to happen.

GAZETTE: Your comment in The Lancet mentioned “major setbacks” in reducing poverty, hunger, and disease. What is the status of global health today, and has the intense focus on COVID-19 globally hurt efforts in other areas?

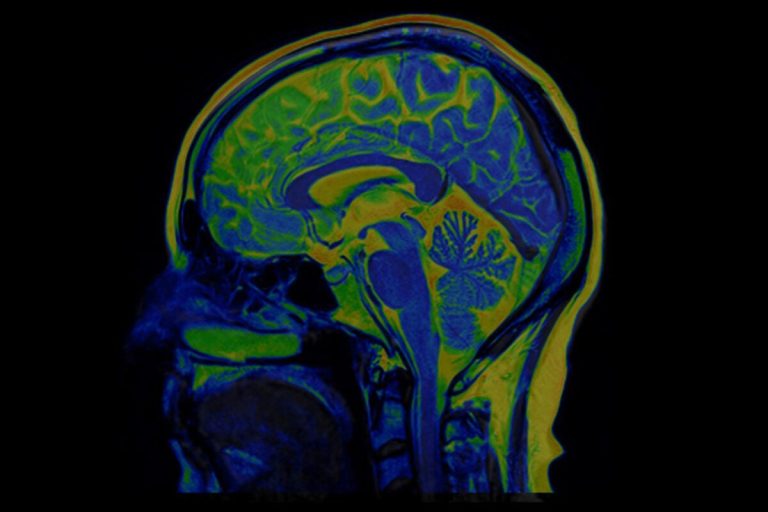

WILLIAMS: Public health connects the dots between structural problems such as poverty and racism and a range of poor health outcomes, including increased risk of complications and death from COVID-19. The pandemic has put the spotlight squarely on the primacy of public health, so when speaking to the current status of global health, we must take into consideration the social determinants of health as well. Among the most critical areas in need of attention are education, food systems, environmental protection, economic stability, and behavioral and mental health.

GAZETTE: Clearly COVID-19 is the most pressing health concern today, both in the U.S. and globally. Are there resources available to address these more traditional health concerns and COVID at the same time, or have public health leaders been forced to choose?

WILLIAMS: We speak about the “COVID slide” in terms of the learning losses suffered by students, but the term can be applied to global health as well. The need to take an all-hands-on-deck approach to the pandemic has meant that other pressing public health efforts have been waylaid. In July, for example, the WHO released a report showing that prevention and treatment efforts for noncommunicable diseases have suffered during the pandemic.

And public health leaders are only human, after all. We are seeing exhaustion and burnout not just among frontline health care workers, but among public health experts as well. For many, there are only so many hours in a day to devote to causes other than COVID-19.

Long before the pandemic began, the U.S. public health system was severely underfunded but now the world has seen what a failure to invest in public health really means — and not just in lives lost. COVID-19 has also represented the greatest threat to value creation since World War II. Having now been brought to our knees, we need to stop making do with less and instead start investing more in public health infrastructures — not only for our collective well-being, but for our economic health as well.

“We believe it’s important for the Biden administration to build on the tradition of U.S. humanitarian leadership, not just because the world needs it, but because the world is waiting for it.”

GAZETTE: You and your co-authors mention a variety of steps to fight COVID-19. How, in your mind, can the U.S. most effectively help efforts abroad?

WILLIAMS: First and foremost, the U.S. should do everything it can to regain its leadership role in the world. This means leading by example, certainly, but also leading by investing in key initiatives that ensure our collective safety in a way that recognizes our interconnectedness. A threat anywhere is a threat to all of us, and this is true for viral threats as well as inattention to, say, planetary sustainability.

The incoming administration could make an immediate, meaningful impact across several areas, such as mobilizing partners to fund the U.N. COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP) to re-engage with and strengthen WHO. WHO covers a whole range of global health threats, from maternal and child health to noncommunicable diseases and universal health care. However, WHO’s $5.8 billion biennial budget falls far short of its enormous global mandate. Of course, all of this in addition to working to ensure equitable worldwide distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

GAZETTE: Given the U.S.’ dismal record fighting COVID-19, why is U.S. help needed and is its “leadership” even wanted?

WILLIAMS: With innumerable health crises worldwide, U.N. humanitarian appeals are facing massive deficits. As the wealthiest nation in the world, the U.S. has the means and the resources to help bridge this gap, and we must begin to do so as soon as possible. COVID-19 has proven U.S. interests are linked to global health security, and international cooperation related to COVID-19 could become a model for defeating other global health threats. We believe it’s important for the Biden administration to build on the tradition of U.S. humanitarian leadership, not just because the world needs it, but because the world is waiting for it.

GAZETTE: The Trump administration’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization was well-publicized. What are your recommendations for Biden with regards to WHO?

WILLIAMS: Placing WHO in this untenable position was enormously destructive. As Sen. Patrick Leahy put it this spring, “Withholding funds for WHO in the midst of the worst pandemic in a century makes as much sense as cutting off ammunition to any ally as the enemy closes in.” In reality, it’s even worse than that. It’s cutting off our own ammunition, our armor, and our battle plan — not to mention our reserves for the next conflict.

The U.S. must not add to the politicization of WHO. Instead, along with other member states, the U.S. should work toward maintaining the scientific integrity and neutrality of WHO. Biden can help strengthen WHO, not only for the response to COVID-19, but also for the full range of health issues. The fact is, most of the money the U.S. provides is not earmarked for emergency response or outbreak mitigation; instead, the majority of these funds go to essential global health programs like polio eradication, mental health initiatives, and cancer and heart disease prevention.

“WHO’s annual budget is less than that of most university hospitals. And yes, WHO did make mistakes at the outset of the pandemic, but so did many other organizations and countries.”

GAZETTE: Is reform of WHO needed? Are any of the Trump administration’s criticisms of WHO well-founded?

WILLIAMS: Reform of WHO is absolutely needed, for it was not designed to be independent, nor is it vested with the power or resources it needs. In fact, WHO’s annual budget is less than that of most university hospitals. And yes, WHO did make mistakes at the outset of the pandemic, but so did many other organizations and countries. As for China’s undue influence and the U.S. response of pulling the plug, in both cases, bold political bullying was in clear effect. Through reform and proper funding, the WHO can play an even more meaningful role in global health. Too many countries, especially poor ones, depend on WHO for medical guidance and supplies and need this assistance now more than ever.

I would also be remiss in not mentioning how delighted I am with the choice of Dr. Rochelle Walensky, M.P.H. ’01, to lead the CDC. Her appointment represents a renewed investment in the scientific and humanitarian assets that can be brought to bear on both domestic and global public health pursuits.

GAZETTE: You mention acute hunger doubling in 2020. Why is that and how much damage has been done to efforts to end hunger? Are there solutions?

WILLIAMS: The World Food Programme (WFP) projects a doubling of children and adults facing acute hunger globally by the end of 2020. Beyond illness and death, this virus has had a tremendous impact on the global economy, supply chains, food supplies, and access to humanitarian aid. COVID-19 has created a pandemic on top of a pandemic — food insecurity is a real and present threat all over the world. To address this crisis, we need long-term policy solutions to hunger, food waste, and climate change. Food donation is only one piece of the puzzle. Countries must bridge the gap between surplus food and the growing need for food for the most vulnerable. (One-third of all food produced for human consumption goes to waste, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.)

In terms of solutions, we need a globally coordinated, multifaceted effort. Here in the U.S., a new stimulus bill must include an increase in SNAP benefits [formerly known as food stamps] for families — and such a bill should be passed as soon as possible. The safe reopening of schools and day care centers around the world would also make a huge difference, in part because so many children receive meals there. The pandemic has also caused a disruption in food supply chains that will need to be addressed on a global scale.

This spring, the Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the World Food Program, and the World Bank put out a joint statement calling for collective, international action to ensure that our food supply chains are not further threatened by the pandemic and that we begin work now to avoid future disruptions to our food and agricultural systems.

GAZETTE: What about slowed childhood vaccination efforts? That seems an area whose potential consequences are severe.

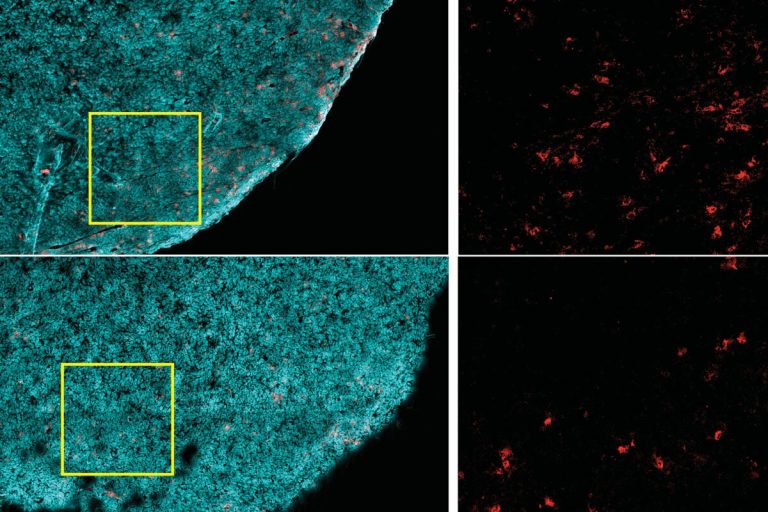

WILLIAMS: The slowing of childhood vaccination efforts will undoubtedly have long-term, dire consequences. COVID has disrupted the ability of global health care systems to deliver routine, preventative vaccinations; parents are also restricted by lockdowns and the fear of contracting COVID in a doctor’s office. The delayed transportation of much-needed vaccines is exacerbating the situation. Since March 2020, routine immunizations have been scaled back in the extreme. According to data from WHO and UNICEF, the lack of vaccinations has put at least 80 million children under the age of 1 at risk for diphtheria, polio, and measles. Child vaccination campaigns have also stalled, even as measles deaths increased by 50 percent from 2016 to 2019. And that’s before we even get to the U.S. The irony of having the most effective vaccination programs known to mankind attenuated during the pandemic is not lost on me. We can and must do better to assure the stability of programs like childhood immunization programs during times of duress.

All of this comes also before we’ve even talked about vaccinating children against COVID-19. There are so many issues we will need to confront in terms of introducing children and adolescents into clinical trials, and which age groups should get vaccinated and when. The last thing we need in our fight against the pandemic is to see an unnecessary delay in children receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.

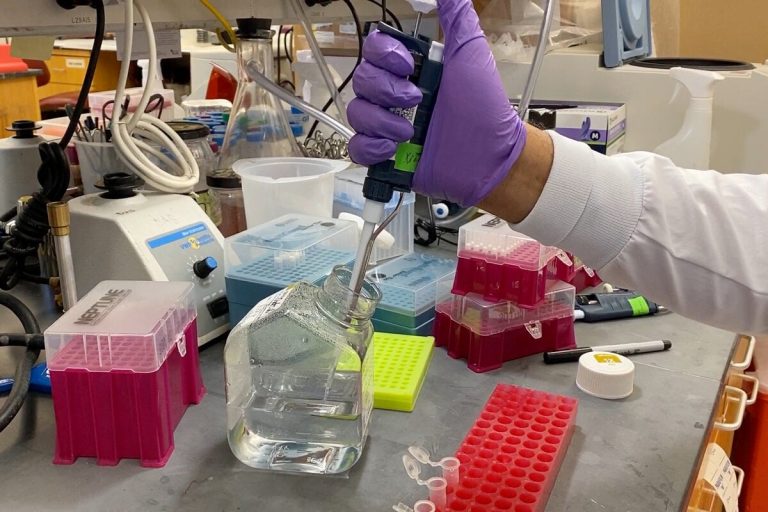

GAZETTE: You call for an increase in the domestic research and development budget by $1 billion. Why is that needed? Hasn’t an enormous amount of money flowed into disease research this year?

WILLIAMS: It’s not just about the size of the research and development; it’s about where and how it’s spent in order to bring forward the best outcomes. There are areas in domestic research that have been chronically underfunded, and we are paying the price by not having strong evidence upon which to build public health programs and to generate new policies. For example, it has become very clear that we need an evidence-based approach in the behavioral and communication sciences. In particular, we need better data to inform how to overcome misinformation and, for example, how to promote vaccine acceptance. We can celebrate what the STEM fields have brought forward all we want, but if we don’t have the investments to inform vaccination campaigns that are confronted with the clear and present danger posed by misinformation, that is going to be a real public health challenge in the months ahead.

To accelerate scientific advances, we will need to increase domestic research and development funding by at least $1 billion annually, as the National Academy of Medicine has recommended. Research and development help us attack the world’s most pressing global health challenges and make major health improvements worldwide. We will always need cutting-edge technology, drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics — without these innovations, we will not be able to unleash science to combat global health risks. We must stay ahead of the curve, on infectious disease most especially.

GAZETTE: You also call for renewed focus on climate change, which Biden has indicated he supports, and on microbial drug resistance. Climate change has gotten a lot of attention recently. Why do you think microbial drug resistance is as urgent?

WILLIAMS: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens our ability to treat common infections and increasingly threatens the health of people both in the U.S. and globally. Back in 2016, the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance concluded that by 2050, drug resistance would claim 10 million lives a year and would wipe out a cumulative $100 trillion of economic output. Here in the U.S., the CDC has estimated that 2 million people will suffer drug-resistant infections every year, and that 23,000 will die — and those numbers are considered underestimates. In other words, we simply cannot afford to ignore AMR. The Biden administration should incentivize pharmaceutical and biotech companies to develop new antimicrobials and support multilateral efforts to confront antimicrobial resistance. In the context of pandemic preparedness, nothing is more important.

In fact, antimicrobial resistance represents one of the greatest public health challenges of the 21st century, one in which I am confident we will eventually prevail. We will do that in the same way we have historically triumphed over other public health threats, from infectious diseases to drunken driving: through a sustained, coordinated, multifront campaign.